Kevlin Henney’s 1968 talk introduced me to “Notes on the Synthesis of Form” by Christopher Alexander.

I incorrectly assumed, that a book which was written in 1964, using architecture as a basis for the abstract ideas surrounding the design process, would not be able to teach me anything about software development.

I feel that his thoughts also capture what a lot of software engineers/designers/developers/etc go through in their daily work, and that it offers insights into the core ideas around problem solving.

I won’t attempt to comment on all aspects of the book, but there are two processes for design that he highlights; the unselfconscious process and the self-conscious process which I have some thoughts on.

Synopsis

“These notes are about the process of design; the process of inventing physical things which display new physical order, organisation, form, in response to function.”

This is basically what the book is about. Identifying the existing frameworks of applied design principles. Although we don’t tend to think of software as a physical thing, in my mind, the intentions and mechanisms are the same.

We, as people who write software, are bringing in to existence something concrete that didn’t exist before. We have the luxury of being able to change the things that we build with relative ease compared with say, the fundamental structure of a bridge or a 20-story apartment block, but it is something worth bearing in mind as part of the design process.

My purpose isn’t to cover the entire book in detail. There are certain aspects that I felt resonated with me and have practical applications in the way we go about our daily work.

Design Problems

“Today, function problems are becoming less simple all the time. But designers rarely confess their inability to solve them. Instead, when a designer does not understand a problem clearly enough to find the order it really calls for, he falls back on some arbitrarily chosen formal order. The problem, because of its complexity, remains unsolved.”

This is the second paragraph in the book, and it packs in a huge amount of interesting and relevant information. It acknowledges that:

- Entropy is increasing.

- People have a hard time admitting to their shortcomings when solving problems.

- Solutions to problems call for “order” and “structure” which don’t yet exist.

- People fall back to what they know and/or apply someone else’s model in the absence of an already existing good solution.

The first chapters set out the idea of a design problem, which I see as: when you have multiple values brought into conflict by your list of requirements, you have a design problem.

This happens in software all the time. You want to have a solution that is fast, maintainable, correct, reliable, robust, etc. And this is just talking about the outcome, which may or may not involve writing code! Maybe these aren’t the values that you’re after, perhaps you have different ones, but it’s the trade-off between these values which will determine how good of a solution it is when it interacts with reality.

What about the process of creating a solution itself? You want it to be pain free, automated, be supported by great tools, enjoyable, be cost efficient, time efficient, easy to change, etc. Again, you might have different values here, but is important to make a distinction between the values you hold for the process and the values you hold for the solution.

Alexander goes on to write in terms of solving problems, that although seem superficial, are becoming complex to the point where the solution is out of reach for a single person. He introduces the idea of using mathematics to assist with the design process.

“It is not hard to see why the introduction of mathematics into design is likely to make designers nervous. Mathematics, in the popular view, deals with magnitude. Designers recognise, correctly, that calculations of magnitude only have strictly limited usefulness in the invention of form, and are therefore naturally rather skeptical about the possibility of basing design on mathematical methods.”

“What they do not realise, however, is that modern mathematics deals at least as much with questions of order and relation as with questions of magnitude. And thought even this kind of mathematics may be a poor tool if used to prescribe the physical nature of forms, it can become a very powerful tool indeed if it is used to explore the conceptual order and pattern which a problem presents to its designer.”

This really spoke to me - understanding that there are formal laws and methods that allow us to scrutinise objectively the order and design of a solution both independently and dependent on the context, is a very useful tool.

How well does your programming language of choice assist you in getting to the right solution? How many solutions that you build with your current tools and process end up aligning with the values that you wanted for the outcome?

If your answer is “not often”, then make an opportunity to learn and use other tools and paradigms. Taking different approaches to the problem will bring different values to the solution inherent in their design.

By doing this, I can guarantee that you will be surprised at how different it feels to internalise the new paradigm’s intent compared with attempting to adapt it’s models into your existing tools and processes.

What is the definition of “a solution”?

Alexander outlines a way in which to best describe what a solution or desirable outcome is for a particular problem.

He states that we do this, by recognising things that seem out of place. If we are unable to notice any more parts of a solution that are out of place, then we can say that that the solution to the problem is of “good-fit”.

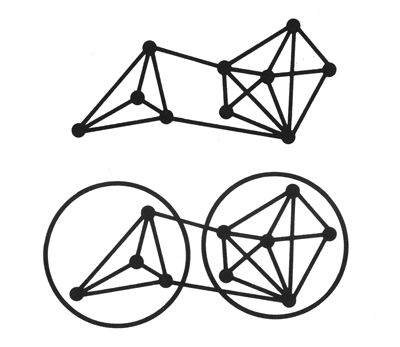

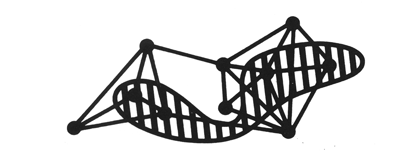

An interesting observation about “solutions” is that they can change and adapt over time. One of the key points he makes the need for “subsystems that can independently change at a different rate with minimal effect on the other parts of the system” as to not cause instability or collapse of the system.

We know this in the software industry well. Decoupling, modularity, group code by their rates of change, ensure that you operate at the same level of abstraction inside the outer context that you’re currently in, etc.

The following quote captures how it feels to work on software where attention is given to the direction of the software architecture. But this also applies to teams, building relationships, self improvement and most other areas of life that deal with complex living systems.

We may therefore picture the process of form-making as the action of a series of subsystems, all interlinked, yet sufficiently free of one another to adjust independently in a feasible amount of time. It works, because the cycles of correction and re-correction, which occur during the adaptation, are restricted to one subsystem at a time.

The image below shows what often happens when attempting to create a solution that isn’t isolated to subsystems that are local to each other. We’ve all seen, worked with, and have built solutions like this and we know what they feel like to work with. It is extremely difficult to evole one sub-section of the system, without having other critical parts of the infrastructure failing due to unintented side-effects.

So, given the definition of what a solution is - both “good-fit” and a linked series of subsystems, Alexander goes on to describe to two processes that lead to the creation of a form.

The unselfconscious process

This is best described as the method of tradition and evolution over time in the hands of the creators.

Some of the characteristics include:

- people are shown how to build the form and accept it without question.

- the process has evolved slowly over time with only minor corrections of the form, performed by the experienced people interacting with the construction of the form in that moment.

- can only respond to a slow rate of change.

- this process fails when presented with complex choices requiring the invention of new forms from scratch.

This method of the unselfconscious process is proven to be effective at producing forms of best fit.

The key mechanism that makes this process produce well-fitting forms is the ability for anyone to make corrections where they see a mismatch of form to solution, immediately and autonomously.

“The failure or inadequacy of the form leads directly to the action. This directness is the second crucial feature of of the unselfconscious system’s form-production. Failure and correction go side by side. There is no deliberation in between the recognition of a failure and the reaction to it.”

The other key aspect here is the amount time spent with the same problem. It is over generations, in which the problem context does not shift, so the people working with the solution have the time to adjust it to fit the problem over time. They notice more of the subtle “misfits” over time and make corrections as they learn more about the context in which the problem exists.

What are some industries that you can think of which evolve over time in this manner either in the past or present-day?

The self-conscious process

This is the method of abstract analysis, pattern recognition and compression of information so that it may be transferred quickly to others, objectively debated and modified rapidly.

“As it stands, the self-conscious design procedure provides no structural correspondence between the problem and the means devised for solving it. The complexity of the problem is never fully disentangled, and the forms produced not only fail to meet their specifications as fully as they should, but also lack the formal clarity which they would have if the organization of the problem they are fitted to were better understood.”

There is a clear trade-off at play here. That we can mostly create forms that seem to fit for a short time, but they start to fail because of this lack of structure in the problem solving process itself.

So, although the self-conscious process is something that allows for extremely rapid change in a turbulent environmental context, the thing that suffers is the form itself; never having a chance to reach “good fit” for the context and ultimately resulting in a constant churn rate that is self-perpetuating.

In my journey as a software engineer, I can’t say that I’ve felt that the two processes like a binary mental switch and I certainly don’t feel that this would be the case generally. It feels more like different parts of your process to create a solution (communication, tooling, relationships, technical, etc) live in the unselfconscious mode and others in the self-conscious mode.

Why does this matter?

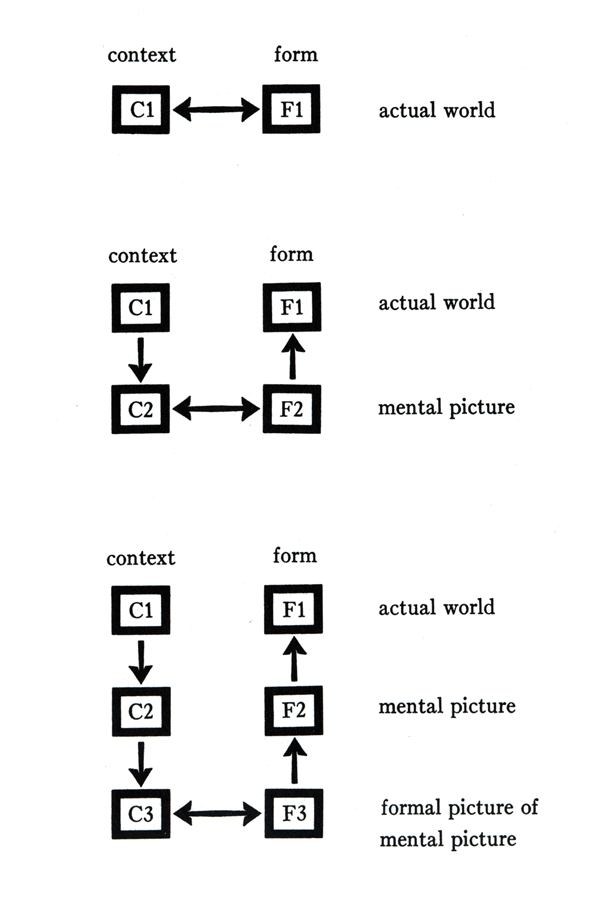

Communication. Or rather - miscommunication.

As we strive to write code to solve complex problems over time, we need to formulate a mental picture of what the problem actually is. The next step, is that we also need to formulate a mental picture of the solution.

Here’s what Alexander has to say about this.

“In the unselfconscious process there is no possibility of misconstruing the situation: nobody makes a picture of the context, so the picture cannot be wrong. But the self-conscious designer works entirely from the picture in his mind, and this picture is almost always wrong.”

If you think about all of the problems that you are working on every day, in every context and in every part of your ecosystem, you’ll start to realise as I have, that having formal, unambiguous methods for coming up with solutions that can be shared with other people with the minimal amount of misunderstanding will mean that you remove an element of what seems to feel like exponential chaos in your pursuit of coming up with solutions that can evolve and stand the test of time.

Referencing the talk (1968) that I mentioned at the beginning of this post, there is a lot we can learn from people in our industry who have come before us.

Think about how you can be a part of the creation of forms that can achieve “good fit” by leveraging what has already been learnt, experienced and formalised - otherwise you will be subjected to much frustration as you attempt to come up with solution models to your problems that will almost certainly be incorrect.

This isn’t to say that it can’t be done - just that the likelihood of achieving a model which is of “good fit” from just your mind alone, in complex systems with increasing entropy, is highly improbable. And if you acheive this, then you still need to formalise it so that it can be communicated to others. This was a big realisation for me.

We are fortunate that we work in an industry where automated computation is something that we get to interact with and manipulate directly. With this proximity, if we can focus on encoding more provable abstractions along with logic and reasoning into our software in a clear and unambiguous communicative manner (via mathematical laws perhaps), then we can leverage the already existing developed field of mathematics (and more) for describing and working with our codified solutions in a more productive and direct way with both the problem context and our peers.

Be curious, read and learn about other paradigms, learn about the values that others held in their minds as they attempted to solve similar problems with a different focus or alignment of those values.

Closing thoughts

After reading the book, I’ve attempted to make sense of the abstract concepts in terms of my current involvement in software and the pain points that come up each day.

There are many other insights that this book provides, which I will attempt to cover in following posts such as system cohesion, developing a structure for solving a problem (given a context), how social communication structures impact a solution - and perhaps a comparison of some software engineering paradigms in reference to this material.

I plan to review these ideas again in six months to a year from now to see if my intuitions and correlations to software make sense, and how they might help others in their journey.

As always, I hope this is useful information to you and thanks for reading!

If you like this post and want to get in touch, please reach out and follow me on Twitter.

Special thanks to Jack Kelly and Wesley Moore for helping me review this post.